By Jordan Schaul | National Geographic | Summer 2010

More than a century after they were driven from the wild, wood bison, a close relative of plains bison and the largest mammal in North America, are set to make a comeback. If all goes according to plan, the first wood bison could be released into Alaska’s interior as early as 2012.

Photo by Doug Linstrand/courtesy of AWCC

More than a century after they were driven from the wild, wood bison, a close relative of plains bison and the largest mammal in North America, are set to make a comeback. If all goes according to plan, the first wood bison could be released into Alaska’s interior as early as 2012. By Jordan Schaul...August 12, 2010

More than a century after they were driven from the wild, wood bison, a close relative of plains bison and the largest mammal in North America, are set to make a comeback. If all goes according to plan, the first wood bison could be released into Alaska’s interior as early as 2012.

By Jordan Schaul

The Alaska Wildlife Conservation Center (AWCC) has partnered with the state of Alaska (Alaska Department of Fish & Game) and a wide variety of other conservation groups on a wood bison restoration project, and are preparing to reintroduce wood bison (Bison bison athabascae) to interior Alaska more than 100 years after their extirpation in the state.

Wood bison, the largest mammal in North America. Click on photo to enlarge the image.

This effort will not only increase the worldwide population of wood bison, but will be a significant event in northern ecosystem restoration efforts, resulting in the reestablishment of a keystone grazing herbivore to what were once natural-grazed ecological communities. Wood bison are a close relative of plains bison and are the largest land mammal in North America.

Wood bison are well-adapted to northern meadow and forest habitats. While they consume a variety of plants, the majority of their diet consists of grasses and sedges. Although changes in habitat distribution, which caused populations to become increasingly isolated, probably contributed to their demise, large amounts of suitable habitat are still available in interior Alaska.

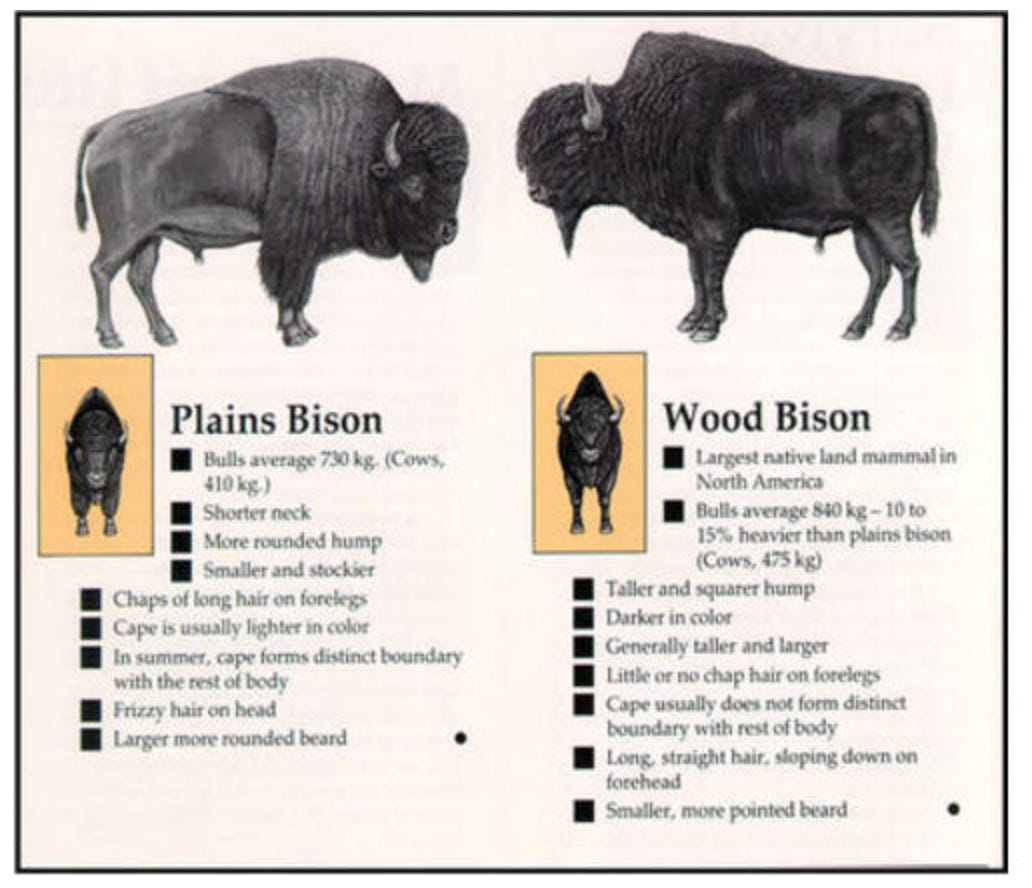

Comparison of wood bison with plains bison. Click on the chart to enlarge it.

Chart courtesy of AWCC

Unregulated hunting is considered a primary reason for their extirpation in Alaska and Yukon, and hunting associated with the westward expansion of European settlers and the fur trade caused a rapid decline and near extinction of the remaining populations in Canada during the 1800s.

Although plains bison were introduced in a few places in Alaska several decades ago, they are not a native subspecies. In addition to different herd social dynamics, several morphological features distinguish wood bison from plains bison.

Wood bison are currently listed as an endangered species under the Endangered Species Act (ESA), but this status is likely to change. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) may designate wood bison as a nonessential experimental population under section 10(j) of the ESA, which would allow the state and federal governments greater flexibility in managing wood bison in Alaska.

USFWS is also completing a status review and may down list or delist wood bison, based on the substantial improvements in their status since they were listed as endangered about 40 years ago.

In hopes of promoting more sustainable free-ranging herds of wood bison, Canada’s National Recovery Plan (pdf), the IUCN/American Bison Specialist Group and a number of state and national conservation organizations in the U.S. recommend that wood bison be restored to one or more parts of their original range in Alaska.

Wood bison at Alaska Wildlife Conservation Center.

Photo by Doug Linstrand/courtesy of AWCC

Captive wildlife facilities like the Alaska Wildlife Conservation Center play a critical role in facilitating restoration efforts which may be intended to augment wild populations deemed vulnerable to extinction because of a host of factors from over hunting to habitat loss to disease.

These wildlife centers also facilitate the reintroduction of a population like this stock of wood bison which will serve to reestablish the subspecies in part of its historic range. In some cases captive facilities serve not only to hold wild-caught individuals that will be later released into available habitat, but they serve as holding and breeding facilities to propagate new generations of offspring designated for release.

The AWWC received wild wood bison from the Yukon in 2003 and witnessed its first calving season in 2005.

At the AWCC we facilitate recovery through both translocation and reintroduction efforts while also contributing to conservation through formal and informal education of patrons. Visitors to the Alaska Wildlife Conservation Center get an opportunity to see a herd of wood bison up close in natural enclosures along with other native ungulates and carnivores, some of which are displayed in what are known as mixed species exhibits.

As I corralled and herded wood bison cows and calves for a health check with fellow staff from AWCC, in late June, I saw two of our coastal brown bears and a grizzly sow suddenly move out of the bush into a clearing along the perimeter of the bears’ 18-acre enclosure. All were following single file with the lead animal attaining bursts of high speed in the direction of the bison calf. It kind of gave me chills reminding me of why I always tried to be on the right side of the fence as a bear keeper.

Not only did this sudden moment demonstrate the deeply engrained predatory instinct of the brown bears, but it suggested how vulnerable these ungulate calves are once separated from their mothers, even if for just a brief period of time.

I looked at the calf in front of me. It was understandably nervous and truly hopeless. And I peered back at the bears watching me and this calf. You could see how the musculature of the huge carnivores standing 15-20 meters away permits them to attain short bursts of speed for taking down moose and caribou calves.

One day wood bison calves may again become a part of their prey base. I was just glad that I was in the pasture with the bison, as unhappy as they were to have me there.

Some facilities designate staff positions specifically for experts in restoration biology. Two of my esteemed colleagues at the world famous San Diego Zoo are leading authorities on captive management and species reintroduction programs.

Ron Swaisgood, the director of Applied Animal Ecology at the San Diego Zoo’s Institute for Conservation Research has led efforts to restore species such as California condors, San Clemente Island loggerhead shrikes, Caribbean rock iguanas, mountain yellow-legged frogs, giant pandas, several bear species, rhinoceroses, and Stephens’ kangaroo rats.

This past spring, Ron sent me his then recently published article addressing some of the critical preconditioning efforts captive wildlife facilities undertake to prepare animals for a life in the wild.

The article entitled “The conservation-welfare nexus in reintroduction programmes: a role for sensory ecology” was published in the May issue of journal Animal Welfare (Volume 19, Number 2) and reviews applied tools and new perspectives for restoration specialists and zoo animal care professionals. Upon preparing this article, Ron was unavailable to comment, but he will continue to be a resource for us as a reintroduction biologist.

As much as animals need to be able to cope with stressors at the point of release, we need to give them a jump start by make sure they are in good body condition. This starts with the husbandry experts like my employer, Mike Miller, the founder and executive director of the Alaska Wildlife Conservation Center. Despite my own background servicing beef and dairy cattle operations, and work with domestic breeds, as well as anoa and banteng in captivity, I defer to Mike who has 20 years of experience raising plains bison and woods bison, which are substantially larger than the wild bovids I mentioned.

There is some book knowledge involved, but the hands-on daily experience is invaluable to pre-conditioning/pre-release programs.

AWCC video about bison restoration program.

KTUU video about wood bison (March 18, 2009)

Another distinguished colleague from the San Diego Zoo would likely agree. I like to pick his brain for his husbandry expertise, but Carmi Penny, the director of collections husbandry science and curator of mammals at the San Diego Zoo is as much a husbandry specialist as a conservationist.

He was just as eager to get a progress report on our recovery efforts. The San Diego Zoo currently owns wood bison (currently on loan to another facility) and they have a vested interested in recovery efforts for this lesser known northern subspecies of bison.

Carmi asserts that “Zoos and related facilities have an opportunity to participate in ground-breaking conservation initiatives as the Alaska Wildlife Conservation Center has with wood bison on this noteworthy restoration project.

“Zoos and aquariums and other captive wildlife facilities are equipped with unique animal care knowledge, training in preventive and clinical veterinary medicine and the management skills gained from working with small populations in restricted spaces to contribute to restoration biology programs for endangered species.

“Zoos can transfer their ‘zoo-biological’ science and broad animal management experience to assist in the breeding of new stock for release programs.”

Carmi added that “[Their] animal training staff can help in the conditioning of animals for successful release along with keepers, curators, veterinarians and in-house research ecologists and animal welfare specialists. Additionally, zoos can support restoration efforts by raising public awareness of the needs for functionally sound and ecologically biodiverse landscapes by sharing compelling stories with zoo visitors. They also help by providing financial as well as personnel resources for such conservation efforts when needed.”

“THE EXTIRPATION OF WOOD BISON FROM ALASKA REMOVED THE ECOLOGICAL FUNCTIONS PERFORMED BY BISON HERDS INTERACTING WITH THE ALASKAN LANDSCAPE.”

In an eloquent narrative he further described the ecological impact of wood bison: “The extirpation of wood bison from Alaska removed the ecological functions performed by bison herds interacting with the Alaskan landscape.

“The physical and mechanical impact of bison on landscape ecology is most significant. The tilling of the soil by the bison herds aided in fertilization of the earth, as the waste from these giants replenished vital ingredients for natural processes.

“Essentially the bison provided a tree sapling removal service that helped keep grasslands as grasslands. As they wallowed in the substrate the depressions created microhabitats for a variety of plant and animal species. And of course their grazing helped maintain healthy grassland diversity.

“In their absence, a functional grassland ecosystem balance reached over millennia of evolution and adaptation had been disrupted.”

If things go as planned for us, we will turn the wood bison, which have just been certified as disease free over to the Alaska Department of Fish & Game, which now owns the herd. They will release the bison into Alaska’s interior as early as 2012.

Sites that are being considered for the release of wood bison in Alaska. Click on the map to enlarge the image.

Map courtesy of AWCC

The program leaders include wildlife biologists Bob Stephenson and Randy Rogers. Their team has selected the Yukon Flats, Minto Flats and the Innoko/Yukon River area as the three sites that are being considered for the release of bison during the next several years as part of ADF&G’s reintroduction program.

The expansive interior of Alaska is an area bounded by the Alaska Range on the south and the Brooks Mountain Range on the north. This region also includes much of Alaska’s boreal forest ecosystem, which supports a variety of wildlife species, including moose, caribou and Dall sheep that are well-adapted to the long, cold winters of Alaska.

Dr. Jordan Schaul is the founder of Schaul PR Group . He was a regular contributor to pop culture and science publications, including Nat Geo Voices & HuffPost.