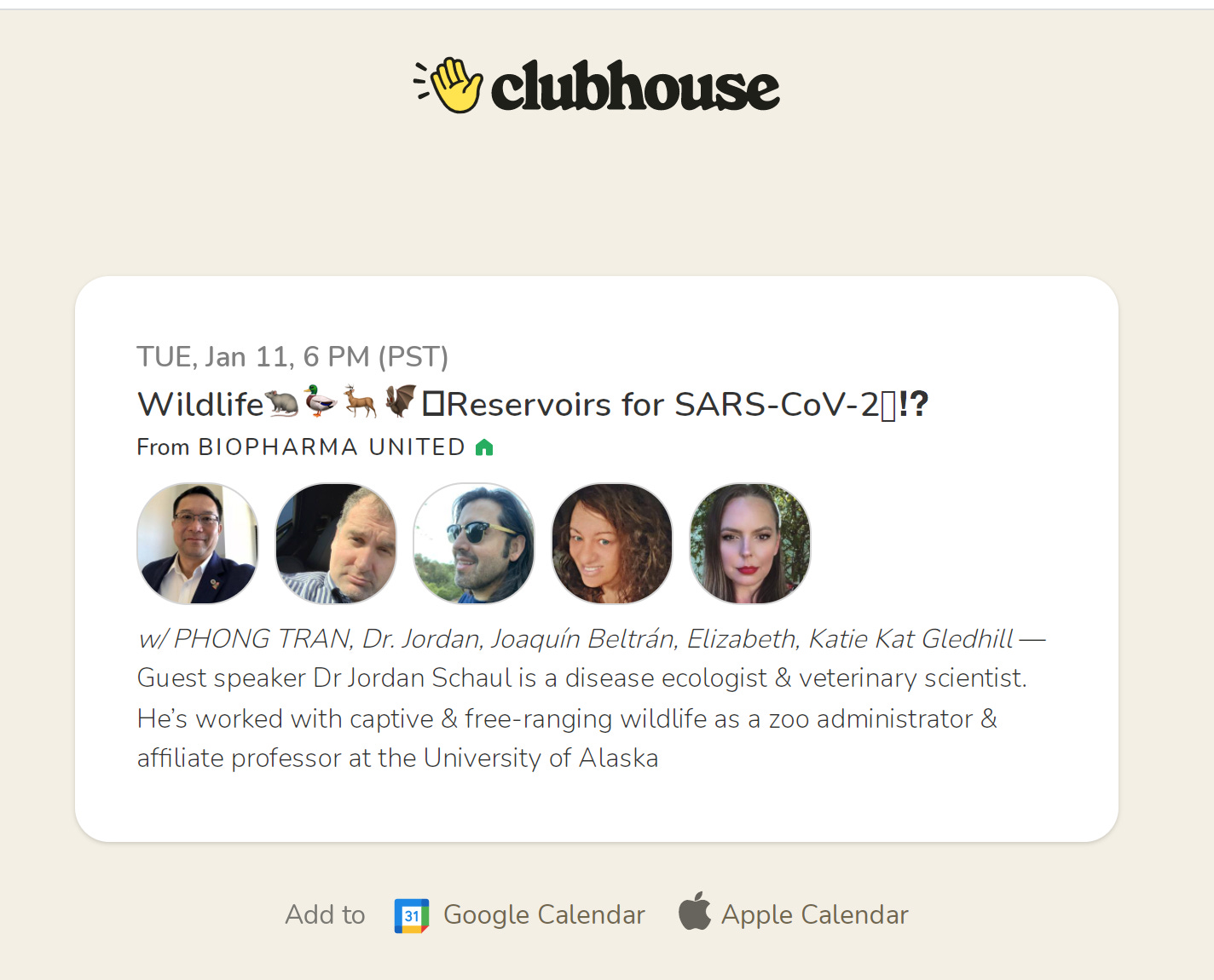

Clubhouse "Covid-19 & Secondary Zoonotic Events

"Reservoirs for SARS-COVID-2" Biopharma United

*Excerpted from “How Zoonotic Spillovers and Spillbacks Threaten Public Health & Conservation-Sensitive Species”

*Phenotypic Relatedness *Geographic Proximity *Novel Host Behavior

anthropozoonosis (animals to humans) = zoonosis

zooanthroponosis' (humans to animals) = anthroponosis

Caleb: Much like the disaster that occurred with mink farms earlier last year, is there a cause for concern when it comes to the health and well-being of these animals?

Jordan: I think it helps to understand some terminology regarding infectious disease spillover events. Zoonotic and reverse zoonotic events are disease spillovers that impact novel or naive host populations. An anthropozoonosis is a pathogen originating in animals that is transmitted to humans in what would be referred to as a zoonotic event.

An anthroponosis is a pathogen originating in humans that is transmitted to animals in what is referred to as a reverse zoonotic event. Following zoonotic spillover events, pathogens may spill back from humans and infect novel nonhuman animal species like mink and deer, and companion and zoo animal species as has already been reported.

Millions of farmed mink were culled in Europe after new variants were discovered following reverse zoonotic events and secondary zoonotic infections reported in their keepers. Consequently, the mink were deemed to pose a threat to public health. By the way, Mink are classified in the family Mustelidae, which includes the likes of weasel, badger, and wolverine and their more highly aquatic cousins (otters). There is concern that feral, farmed, and wild populations of these small carnivorans (mammalian carnivores) and other wildlife species can play a significant role in the ecological epidemiology of Covid.

With regard to farmed mink, there are two reasons why I think they were so susceptible to a spillback event. First, mink are solitary in nature, but commercial populations are bred in small cages housed in close proximity. Secondly, farmed populations exhibit low genetic heterozygosity. The low genetic variability in combination with husbandry practices in fur farms contributes to communicable disease susceptibility.

Some people may not be aware that the farmed mink in Europe and the US and elsewhere are actually descendants of American mink (Neogale vison), which were introduced to Europe in the early 20th Century for commercial breeding. Some animals escaped farms and ultimately established feral populations. which have contributed to the decline of European mink (Mustela lutreola) a Critically Endangered species, which is not farmed. The two species represent different genera and aren’t as closely related as most people think.

Caleb: With increased infection rates being detected across carnivorans in zoos across the country, what seems to be some ideal ways to stop this from spreading to other animals?

Jordan: Surveillance is essential. Vaccination is key. At the very least, testing is conducted on animals and staff working in proximity to animals. I don't know specifics regarding current AZA and ZAA protocols but in general accredited zoos and sanctuaries ensure that staff is immunized and wearing PPE. Any breakthrough infections in staff are dealt with immediately and appropriately. Zoo animals are already quarantined when they move between zoological facilities so in this regard zoos are ahead of the game. In terms of control and prevention within a zoo population, those species deemed most susceptible (cats) are administered two doses of vaccine. I read that Zoetis has donated more than 10,000 vaccine doses to approximately 70 captive wildlife facilities under authorization from the USDA. That is really helpful. But in general, I would say zoo animals are in a better position than some domestic and companion animal populations because so much surveillance work is already conducted on captive wildlife populations because they are sentinels for emerging and re-emerging disease and already had robust preventive health programs in place before the pandemic.

Caleb: Recently, APHIS released data gathered during a study indicating there is an increased infection rate among whitetail deer in America. What are the potential implications of this increased infection among these animals?

Jordan: As I mentioned, scientists are concerned about spillback in domestic and companion animal populations as they are with captive wildlife like farmed mink and zoo populations because of their proximity to people. But free-ranging wildlife and particularly urban wildlife can pose a serious threat because mutations can occur unchecked in these populations that are exposed to people in nature. The reported exposure to and infection with SARS-CoV-2 in white-tailed deer populations is worrisome. If deer become a stable reservoir for Covid -19 they can present the threat of a secondary spillover to humans even if we heavily control or eradicate the disease in people.

Deer and other wide-ranging wildlife populations also present a potential threat to conservation-sensitive species because they can transmit the virus to other nonhuman animal populations they come in contact with. In the cases of active infections and more severe disease, it seems that carnivoran populations, meaning mammalian carnivores like wild cats and mustelids like mink are more vulnerable than deer. I just saw that a snow leopard died in a US Zoo today from Covid and of course, mink have shown signs of respiratory disease and have died. Incidental reports of companion animals succumbing to Covid have also been documented. The concern with deer is that hunters also come in close contact with these game animals and through their exposure handing carcasses they can become infected.